TREMONT SPEAKS

Photo: General Store at Branch Ave & W 14th

Over the years, many Tremont residents have gone “on the record” to discuss their experiences living, working in, or visiting Tremont. Here is a collection of those interviews.

Audio interviews are from Cleveland State University’s “Cleveland Regional Oral History Collection.”

Recorded Oral Histories from CSU

Recorded during Prosperity Social Club’s 10-year anniversary event, Jean Brandt discusses the Tremont community and the important evolutionary role of Dempsey’s/Prosperity.

Greg and Jacquie Dembowski—son and daughter of Richard and Theresa Dembowski—describe their experience growing with their family’s business, Dempsey’s Oasis (now Prosperity Social Club).

Recorded during Prosperity Social Club’s 10-year anniversary event, Richard and Theresa Dembowski (son and daughter in law of pub-founder Stanley Dembowski) talk about Stanley’s acquisition of Hot Dog Bill’s in 1938, how the name “Dempsey’s Oasis” came about.

Jim Duncan recounts his youth growing up in Valley View Housing Estates, the changes he has witnessed in the neighborhood over the past half century, and working as a shoeshine at Dempsey’s Oasis.

Andrew Fedynsky immigrated to the United States as a child and grew up in Tremont. He describes living in Tremont and notes how Tremont changed with each new wave of immigration.

Bonnie Flinner, owner/proprietor of Prosperity Social Club talks about her acquisition of the pub, her growing relationship with the Dembowski family and the Tremont neighborhood, and what she’s learned (and come to love) about managing a restaurant.

Erich Hooper—owner of Hooper Farm, a neighborhood garden that works with area youth—discusses the early days of the neighborhood, and the changes that have occurred there.

Rebecca Kempton covers decades of change in her local neighborhood of Clark-Fulton. In the latter part of the interview she also focuses on the evolution of Tremont.

Walter Leedy, professor of art at Cleveland State University, discusses architectural landmarks and WPA art in Cleveland. Toward the end of the interview, he focuses on the WPA collection housed at Tremont’s Valley View Homes Estates housing project.

Bill Leshinetsky, discusses the presence and influence of Ukrainians throughout the Cleveland area. He emphasizes the creation, maintenance, and sculptures within the Ukrainian Cultural Garden, as well as Ukrainians’ significant role in the evolution of Tremont.

John Porter recounts being hired as the first bartender at Prosperity Social Club, and discusses the establishment’s development under the ownership of Bonnie Flinner.

Transcribed / Submitted Oral Histories

Written histories have been lightly edited and republished with permission of the interviewees.

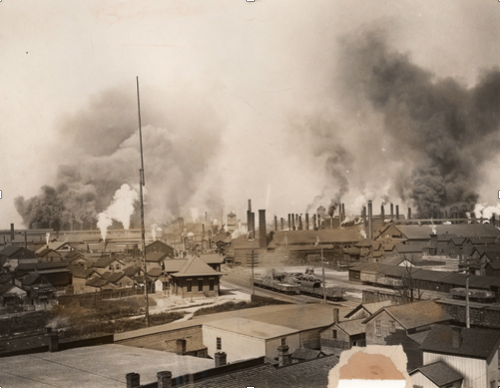

It is impossible to recall my childhood on Tremont Ave. in the 1940s without mentioning the ubiquitous influence of the steel mills. The mills were manifest in many ways, and since I grew up with their presence, they were part of a life I thought was normal. The mills were polluters before there was any meaningful concern for air quality. On many mornings, the sun was filtered through a hazy cloud of industrial particles, sometimes with an accompanying odor. Laundry hung out to dry in the summer was likely to be covered with a light accumulation of soot. The pure-white surface of a winter snowfall would start to turn black in the space of a day. Of course, the preponderance of heating by coal stoves also contributed to the winter soot. In the evenings the sky in the east frequently reflected an orange glow from the fire of the blast furnaces. It was an inescapable part of life for us.

The steel industry, offering enough pay to support a family, was a magnet for unskilled workers. Immigrants working in the mills encouraged friends and relatives from central and eastern Europe to the mill neighborhoods, so it was not by chance that an ethnic neighborhood like Tremont developed near the mills. Workers needed to walk or use convenient transportation to get to their jobs.

My father was one of those unskilled immigrants. Born in Czechoslovakia, he immigrated to the U.S. when he was 21. He learned to speak simple English but was never able to read or write. As with most families living in the South Side, the breadwinner worked in some type of industry. For my dad it was the steel mills. He was a pipefitter at Republic Steel, but I never knew what a pipefitter did. (Years later, when I asked a plumber the difference between a plumber and a pipefitter, he told me that pipefitters don’t have to wash their hands before they eat—nice joke.) My father would come home from work with dirty clothes and, on a couple of instances, with a bandage on his head covering a wound from a falling object. People doing that work these days are required to wear hardhats. A couple of times, fires in the industrial area caused my mother to worry about my father’s safety, but he was never injured.

Payday was on Saturdays, and my dad had to travel via bus into Cleveland and then transfer to a bus that took him the east side. I accompanied him numerous times. I’m not sure exactly where the place was, but there was a bar on the corner of a street leading down a hill towards the steel production area. The building where he picked up his check was a short way down this hill. I don’t think anyone in the South Side had a checking account, so it was important to find a place that would cash your check. Local banks would provide that service, but it was not always convenient on Saturday, so that bar at the top of the hill was frequently the check-cashing place for my dad and others. Perhaps they charged a fee, but that was not something I was aware of. I knew the bar very well because our visits were uncomfortably lengthy for a young child. It was an unwritten rule that if you had your check cashed at the bar, you were obliged to spend some money there. While my dad ordered a shot and a beer, I’d sit at the bar and scan the wall behind the liquor bottles for something interesting to ask for. I usually had a pop and a 5-cent bag of potato chips. One day, I pointed to a small, cellophane package containing some strange dark pieces and asked what it contained. I was soon eating some “blind robbins,” which became a favorite. Blind robbins are smoked herring, preserved with salt, and designed to intensify your need for water (or beer). Blind robbins are not easy to find these days, but they’re occasionally sold in a store’s seafood section in large packages.

After a few rounds and some conversation with his fellow workers, my dad would take me to board a bus that dropped us off on Prospect Ave. in Cleveland. But before transferring to the bus that would take us to our home bus stop on Professor and Jefferson Street, we went to a small store that sold grilled hot dogs. I always wanted mustard and onions on mine. It was one of my favorite experiences because our family never went out to eat. Except for weddings, the only time I ate outside the home was when I shopped with my mom and she bought me chop suey at the lunch counter of the downtown May Company.

The steel mills ran 24 hours a day, seven days a week, three shifts. My dad survived layoffs and strikes and knew he would have a job for the rest of his life—and he did. He died of stomach cancer in 1970, perhaps attributable to the steel mill environment, but who knows?

Shortly after WWII the Cleveland steel industry employed more than 30,000 people. But those were the “good old days.” Over time, strikes, bankruptcies, mergers and competition from foreign steel manufacturers dramatically reduced the presence of the steel mills in Cleveland and across the US. In 2018 the number of employees working in blast furnaces and steel mills for the entire US was only 81,000—down from 137,000 in 2000. Whenever I visit the South Side, I drive down Jefferson or Literary to look towards the old industrial area and reflect upon what used to be.

(This story appeared originally in the July-August 2019 issue of The Tremonster.)

Photo shows Tremont’s neighbor to the east in the 1940s.

Sundays people would gather on the grass and benches in Lincoln Park to chat with friends or play cards, checkers, dominos and chess on the picnic tables. Some would bring picnic baskets from home while others stopped after church. Children played soccer or played at the pond that was in the center of the park. They also had a carousel and swings. Water fountains were at the corners of the park off Kenilworth/W11th and W14th/Starkweather. There were bushes completely around the whole park and Post Lamps that lit up the park at night. They had toilets, but Mom remembers them being dirty. I remember goldfish in the pond and Mike says they broke ground in 1957 to put the swimming pool in that still stands today. Swimming was free from 7 years old and up, but you had to sign in your name and age before getting in. They would check our toes and make us take a quick outside shower spray before getting through the bar gates. Wednesday was Family night for swimming where parents could come. Teenagers would climb the fence and skinny dip late at night. There were Easter egg hunts and band concerts in the park.

Our milk was delivered to our doorstep in glass bottles with cardboard caps. My brother Mike delivered the Cleveland Press and then later turned it over to my brother Bill who turned it over to Roman and me. We raised chickens, rabbits and pigeons in our backyard. We never locked our doors; someone was always home and kids were running in and out all the time. My mom was a cleaning lady and raised 4 children. She paid off her home and has lived in the same house in Tremont for 55 years so far.

The South Side [now Tremont] was home. It was immediate family. It was aunts, uncles and cousins. It was schoolmates whose parents were Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, Slovak, German, Irish, Greek and Syrian. It was a stage deep and wide enough for any dream.

The South Side was St. Augustine’s Catholic Church, St. Theodosius Russian Orthodox Church, Pilgrim Congregational Church, and many others. It was Tremont Elementary School and Lincoln High. It was Merrick House, one of the oldest settlement houses in the city. It was the Dinky, a yellow trolley pretty in memory as a toy. It was Lincoln Park, a square block of grass, trees, playgrounds and benches. A man named Dominic used to sit on a bench, smoke his pipe and talk about the old country and dream about it. It was Fairfield Hill with three and sometimes four layers of children on a sled whistling down the January dark. It was the Jennings Theatre with nickel movie matinees every Saturday and Sunday afternoon, double features every night, and Banko and cash prizes on Saturday.

The South Side was the men who worked in The Flats. It was the men who worked on the railroad, the men who worked in the mills, forges and foundries. It was the women who worked to make ends meet. It was Father Walsh at St. Augustine. It was Miss Bloomfield and Miss Alexander at Tremont Elementary. It was Miss Glick, Miss Palmer and Miss Dickerson at Lincoln. It was the grocer, John, who extended credit all through the Depression. It was Angelo the Jeep, who used to say, even at weddings and funerals, ‘Where is everybody?’ It was TT, who had traveled with the circus, who had survived two wars and two marriages—a solid keg of a man who delighted friends by turning sudden backflips and shouting “Yo.” A woman said, “One of these days you might land on your head.” He replied “That’s the least of my worries.”

The South Side was also Alex, the owner of a small confectionary, a man who took on all comers at two-hand pinochle. Alexander the Greatest, he was called. The South Side was Pete, who now and then during the week before the Fourth of July tossed a cherry bomb in the stovepipe opening of the confectionary, a bomb that exploded with such force in that store it seemed to blow everyone out the door. “What happened?” he would say, innocently. “Ain’t you going to grow up, ever?” Alex would say. It was Romeo, an aspiring actor who tried his luck in Hollywood. He tested for the lead in Golden Boy but lost the role, he said, because he was two inches shorter than William Holden. Long afterward he would say “An inch taller and I’d be dancing with Ginger Rogers.”

The South Side was Danny, who for two years enjoyed one of the sweetest of political plums, a job emptying the wastepaper baskets and dusting the desk, chairs and sofa in the City Hall office of Commissioner Paul, a former shipmate on an ore carrier. Danny would catch the trolley on the South Side at four in the afternoon, hop off in front of City Hall, dash in while the trolley continued its downtown round, do what he was supposed to do, and be out in time to catch the trolley on its way back to the South Side. He would be home by five-thirty. Sometimes he took his wife Vicki to keep him company and do the dusting. Vicki used to say things like, “Haste makes hurry” or “A bird in the bush.”

The South Side was a midsummer night a long time ago with plumes and pillars of smoke in the sky; with flags of blue fire; with a throbbing red glow from the steel mills that could be seen thirty miles away. It was people sitting on porches, porches generous enough for friends as well as family. The women were saying “She outgrew all her clothes” or “I can’t do anything with him . . . . He’s like a wild animal” or “I can’t wait till school starts.” The men were saying “Things are picking up at the mill; I put in three days this week” or “There’s going to be a war; we’ll get in; mark my words now.”

My parents had arrived in Cleveland from Poland in 1916 or 1917 to establish a new life that they. They kept in touch with their parents and from time to time sent them packages and monetary gifts. My mother’s parents, the Bibro family – our mother Mary, her sisters Sophie and Anne and brother Peter—were able to join the family in 1918 but after several years my mother’s mother and sister returned to Poland and never returned. Dad’s family remained in Poland and he was the sole arrival.

I was born in the Tremont area on December 10, 1919 and resided there for 30 years. I then moved to the Brooklyn area after my marriage. Our family resided at 2443 West 7th Street during our childhood and then moved to West 14th Street in 1936. Our neighbors were Guzik, Harchar, Brookes, Proszek, Lestechin, Lapinski and Barr.

The South Side of Cleveland, as the Tremont area was then known, had several ethnic groups: Polish, Russians, Slovak, Ukrainian and a few German families. They all had their churches and community halls, where they gathered for weddings, meetings and other special occasions. The ethnic groups were very clannish and each nationality did its own thing to put it very simply. However, they did get along in a neighborly fashion. People had no fear of being mugged or robbed those days. You could go visit a neighbor, leaving your doors opened, and not be afraid.

Our early years were joyous ones playing the usual games of that era: baseball, roller skating and street games. We also took advantage of the programs at Merrick House. While living on West 7th, we often went to the Lincoln Park Baths and Recreation Center. In the summer, we went to the cabin that Merrick House had in Hinckley Park for a few days where we enjoyed camping and swimming. Lincoln Park was another outlet to visit friends during the hot summer evenings. The movie house at that time was the Jennings Theater on West 14th. We went there frequently on Saturday afternoons to see the Western movies popular at that time. Radios and phonographs were the at-home entertainment sources of the day. We enjoyed them both in the evenings. We had a phone installed in the late 1930s and the first TV came into being later in the mid 1940s.

My brothers and sister attended the parochial elementary school at St. John Cantius. My brother Edmund and I went to Benedictine High School for our secondary learning, Ted went to Lincoln High School and our sister went to Marymount. Both the elementary and high school years were happy years – we were eager to learn and play in class and on the sports field, especially in baseball. All the teachers I had contact with were dedicated nuns, priests and brothers who were proficient and well-versed educators. To choose one favorite teacher would be very difficult. They were all good.

We took full advantage of the West Side and East Side (Central) Markets. In those years, every food, drug, bakery or candy store prospered. Clothing, tailors and furniture stores were nearby and did a brisk business up to the Depression years. Our family had a car at our disposal (one of the few in the neighborhood) and we took advantage of the public transportation when going downtown or to school. Horse-driven vendors came to the neighborhood daily in the summer selling seasonal fruits and vegetables. At that time, 25 cents got you a bag of peaches or apples. Then there was the paper-rex man, who bought old rags.

Nowadays I drive through the neighborhood often and see the many changes. Blocks of homes, homes built on empty lots, and the numerous gourmet restaurants and pubs doing a brisk business especially on weekends. What a welcome change! If other localities in Cleveland would take steps to do what happened in Ohio City and the Tremont area, our city would grow by leaps and bounds. Go Cleveland!